Raising the Profile of Magnetoencephalography (MEG) as a Localizing Tool for Epilepsy

Jeff Tenney, MD, PhD, is one of a growing number of epileptologists who is convinced of MEG’s unique ability to localize seizures. Extensive evidence supports its utility in presurgical evaluations. However, unfamiliarity with the technology’s benefits and indications persists, even in the epilepsy community.

In his new role as president of the American Clinical Magnetoencephalography Society (ACMEGS), Tenney wants to help referring physicians to see magnetoencephalography for what it is: an indispensable technology to localize normal and abnormal brain function.

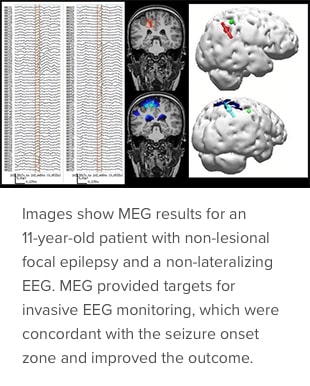

“Only MEG can measure fast, millisecond phenomena and also perform localization accurate to the millimeter level,” says Tenney, who is clinical director of the MEG Center at Cincinnati Children’s. “Some physicians think that if an electroencephalogram (EEG) shows no abnormal results, there’s no need for MEG. But, based on the evaluation of several thousands of patients over the past 10 to 15 years, MEG improves the surgical outcome of epilepsy patients. EEG and MEG go hand-in-hand in a comprehensive epilepsy surgery evaluation.”

The noninvasive test measures the magnetic fields that naturally emanate whenever electric current flows within the neurons of the brain. The fields being measured are extremely weak, about a billion times smaller than the Earth's magnetic field. MEG’s sophisticated instrumentation is sensitive enough to detect these weak signals, while simultaneously discriminating against interference from the much stronger magnetic background noise.

Cincinnati Children’s has been using MEG in the presurgical evaluation of epilepsy patients for 16 years. A new MEG system, installed in 2020, provides a more comfortable environment for patients, who must wear a specialized helmet while lying on a bed for the duration of the test. Inside the helmet, 275 sensors detect abnormal brain activity and identify areas of the brain that are prone to seizures (in comparison, conventional EEG uses only about 20 sensors placed on the scalp).

Tenney and several of his ACMEGS colleagues recently published an illustrated compendium of the 10 most common evidence-supported indications for MEG in epilepsy surgery (Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, Nov. 2020). This resource is a guide for potential MEG users, current MEG referrers and newcomers to MEG related to routine clinical situations in which MEG can add unique, clinically valuable data in selecting surgical candidates. Examples include patients with “spikeless” EEGs and multiple lesions on magnetic resonance imaging.

Only six other pediatric institutions and 14 adult centers in the United States offer MEG, and Tenney hopes that number grows in the years to come.

“At Cincinnati Children’s, we almost always use MEG in our presurgical evaluations for children with drug-resistant epilepsy, and about one-quarter of our patients are referred to us from outside institutions that don’t have MEG,” he says. “The more physicians learn about what MEG can do, the more they realize its potential to localize seizure foci, which can lead to better surgical outcomes and help children with epilepsy experience an improved quality of life.”